The Right to Defend Rights

How Recent Rulings are Protecting Human Rights Defenders in Colombia and Latin America

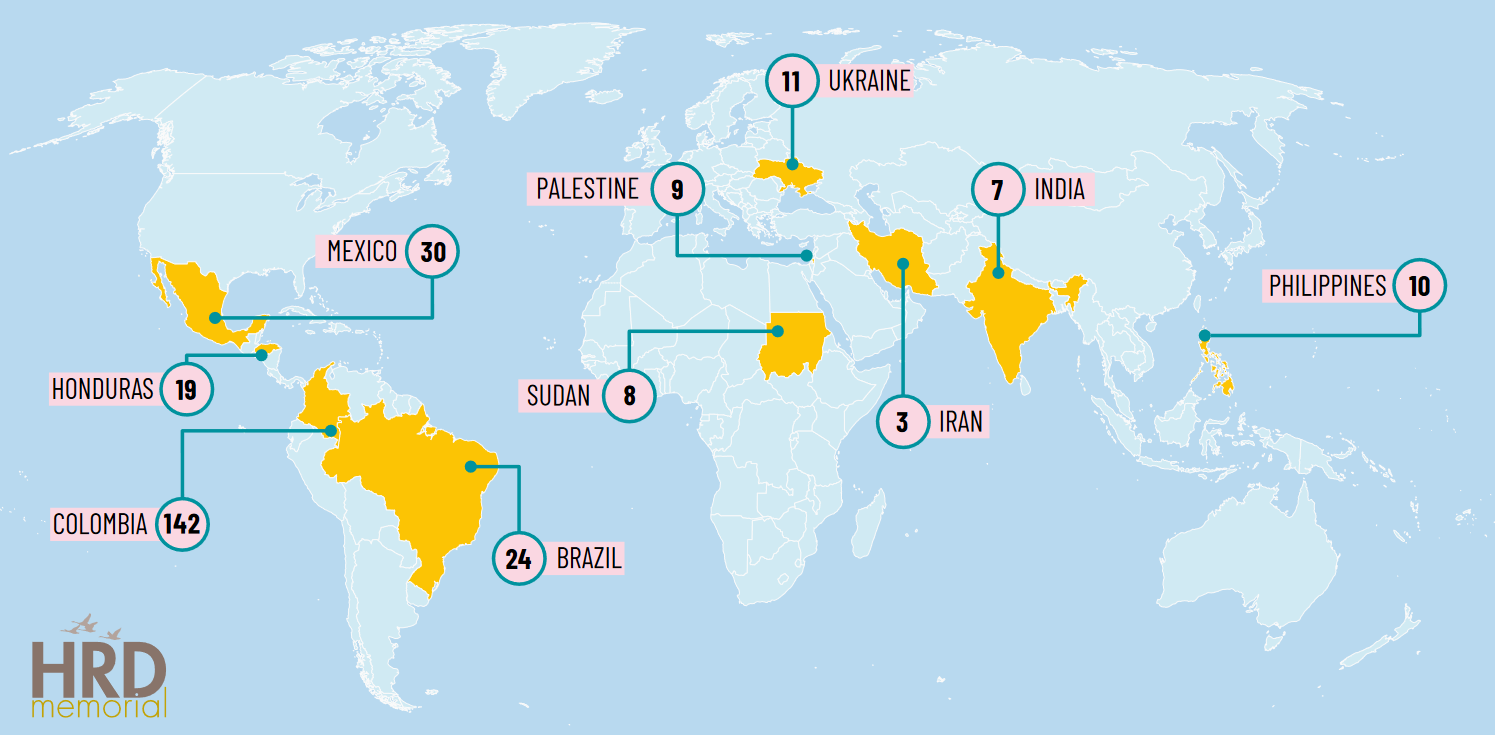

On April 21, Narciso Beleño, a rural (campesino) leader and human rights defender who worked for more than three decades for the restitution of land and the sustainable exploitation of natural resources in Colombia, was murdered. Sadly, this is not an isolated case. According to the most recent report by Front Line Defenders, 79% of the murders of human rights defenders occur in the Americas. Colombia alone accounts for 47% of the deaths of human rights defenders in the world, followed by Mexico and Brazil with 10% and 8%, respectively. Of these fatalities globally, 48% of these individuals were dedicated to defending land, environmental and indigenous rights.

Source: Frontline Defenders Global Analysis 2023-2024

In Colombia, although violence against social leaders may seem indiscriminate, territorial rights defenders are at greater risk. Of 1593 leaders killed since 2016, 20% are indigenous, 15% are peasants and 6% are Afro-descendants. These people had in common that they mobilized around land redistribution, respect for legitimate land tenure and their way of inhabiting it, and the restitution of land that was violently taken from them during armed conflict.

However, the outlook is not entirely discouraging. Two recent rulings by the Constitutional Court of Colombia and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) have analyzed this phenomenon and, in response, have given legal life to the right to defend human rights in Colombia and the region. This does not imply an automatic improvement in the risk to people’s lives, but it is a glimmer of hope in the pursuit of better public policies for the protection of human rights defenders. These decisions are not binding, but they are important precedents that can inspire the regulation of this right in other areas, both regionally and globally.

The Colombian Constitutional Court’s Ruling

Last December, the Colombian Constitutional Court issued a ruling that recognized, for the first time, the right to defend human rights and ordered measures for its protection (SU-546 of 2023). According to the Court, this right has its origin in the 1998 UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders and in the constitutional rights to life, equality, defense and protection, as well as the right not to be subjected to forced disappearance, torture or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. In other words, it is a right derived from international human rights instruments and from the Colombian Constitution itself.

The relevance of this ruling lies in its departure from the classic understanding of guarantees for defenders. In this case, the Court went far beyond simply recognizing the right to physical integrity, that is, the right not to receive physical harm. By examining the cases of 20 social leaders, the Colombian Court concluded that the state had violated four dimensions of the right to defend rights. First, personal security, which had been previously recognized by the Court and which consists of the right not to cause harm, physical or moral, to the person. Secondly, the right to due administrative process implies that the decisions made by the entities in charge of legal protection must be duly justified. Thirdly, the free exercise of leadership implies the right to defend human rights without fear. And fourthly, effective justice, which means that those responsible for acts of violence should be effectively prosecuted and brought to justice.

This ruling was the result of a coordinated action by 20 courageous defenders representing diverse human rights causes of the campesino, Afro-descendant and indigenous population – among others – who, with the support of human rights organizations, came together to demand the legal recognition of the right to defend rights. After more than three years of effort to shed light on the issue, the Court recognized the right and gave it specific content – a step forward in terms of the state’s obligations to open democratic spaces and to guarantee the defense of human rights.

Overcoming the institutional failures that facilitate the violation of the right to defend the rights of territorial and land defenders in Colombia depends on the integration of territorial, ethno-racial and rural approaches in public policy.

The institutional offer of protection that includes bulletproof vests, conventional or armored cars, bodyguards and panic buttons is insufficient. The problem is that these measures do not work in all territories where mobility involves rivers as well as land, or in territories where an armored truck can draw attention to the defender, further increasing their risk of harm. These measures, besides being costly, are designed to protect politicians or businessmen who move in urban areas. They are not adapted to rural contexts where it is difficult to pay for gasoline, the maintenance of a van or the food and hotel of a bodyguard. This is why the state’s protection policies need to incorporate a territorial approach, based on the realities of the country’s rural areas.

Protection services are outsourced to private security companies that decide on the bodyguards for protection schemes. Rural communities, especially ethno-racial ones, have requested that the bodyguards be trustworthy and understand their way of life and the way they defend rights. There have been many cases in which tensions have arisen between the bodyguards and the community to which the defenders belong, due to cultural practices rejected by the majority society. The protection schemes are also designed with an individual focus rather than a collective one, excluding organizational and community protection mechanisms. This also makes clear the need for ethno-racial and rural approaches that take into account different ways of exercising the defense of human rights.

To remedy the situation, the Constitutional Court ordered the evaluation of security measures so that they suit the context and the nature of human rights defense work. This implies taking into account geographical, cultural and armed conflict conditions. Some specific measures dictated by this judgment consist of allowing the hiring of trusted bodyguards chosen by the defenders subject to protection, as well as training processes to ensure adequate provision of security services. They also ordered the state to establish collective protection routes in places where the level of risk for defenders is higher. This opens the way for recognizing other protection measures such as strengthening organizational and community capacities through the media, setting up of safe houses, creating prevention and escape routes, among others.

The IACHR Ruling

Only three months after the Constitutional Court decision on the 20 Colombian human rights defenders was announced, the IACHR issued its landmark judgment in CAJAR v. Colombia, recognizing the right to defend human rights. In an unprecedented judgment in the jurisprudence of the IACHR, the court recognized and defined the scope of the right to defend rights through an evolutionary interpretation of the American Convention on Human Rights.

The Colectivo de Abogados José Alvear Restrepo (CAJAR) is a Colombian NGO dedicated to the defense of human rights since 1980. In this case, the IACHR condemned the systematic persecution the organization has suffered at the hands of the Colombian State. In its analysis, the Court determined that intelligence agencies engaged in improper activities by providing sensitive information to paramilitary groups that then violated the rights of CAJAR members. This created a risky environment for the life and integrity of these defenders, whose rights were violated, including their right to defend human rights. This case is significant because it clarifies that violations can not only come from third parties but also from state agents. Hence the importance of exercising oversight and control over state activities.

With this evolutionary interpretation of the provisions of the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights, the Court recognized the autonomy of the right to defend human rights. Despite its close connection to other rights such as the right to life, to personal integrity, to freedom of expression, to freedom of assembly, the Court indicated that it is a right in and of itself. It translates into “the effective possibility of exercising freely, without limitations and without risk of any kind, different activities and tasks aimed at the promotion, surveillance, promotion, dissemination, education, defense, advocacy or protection of human rights and universally recognized fundamental freedoms” (para. 978).

As reparations, the ruling ordered Colombia to investigate the facts and identify, prosecute and punish those responsible; the implementation of a system for compiling data and figures on violence against defenders; the adaptation of intelligence manuals to comply with international standards and the approval of regulations guaranteeing access to information collected by the state; among other measures.

Their Relevance

The relevance of the right to defend rights lies, in part, in the fact that it is a right and a guarantee on which others depend. It is not possible to speak of the enforcement of human rights if states do not recognize and protect the possibility of promoting and defending them. These two rulings, from the Colombian Constitutional Court and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, are a beacon of hope on the road to building an enabling and less hostile environment for human rights defense. Although the first case is directed at an unspecific group of human rights defenders and the second case addresses the violation of the rights of a NGO, both cases present a series of basic measures and guarantees that could guide and increase the effectiveness of existing policies.

Inspired by these precedents, we trust that states, including constitutional judges, will dare to specify what this right means in each of their jurisdictions. This is particularly important given that within the universe of defenders there are substantial differences in the types and levels of risk, as in the case of leaders who defend territorial rights – as illustrated by the case of Narciso Beleño and so many other campesino leaders who have been assassinated.

The judgments show us that it is possible to recognize this right through an evolutionary interpretation of international instruments such as the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders or the American Convention on Human Rights, as well as constitutional texts. But, above all, they remind us of the vital strength of human rights defenders and organized civil society to achieve a greater commitment of states to uphold human rights and democracy.

This article first appeared in Latin American Spanish on Agenda Estado de Derecho. The article is part of a collaboration between AED and Verfassungsblog.